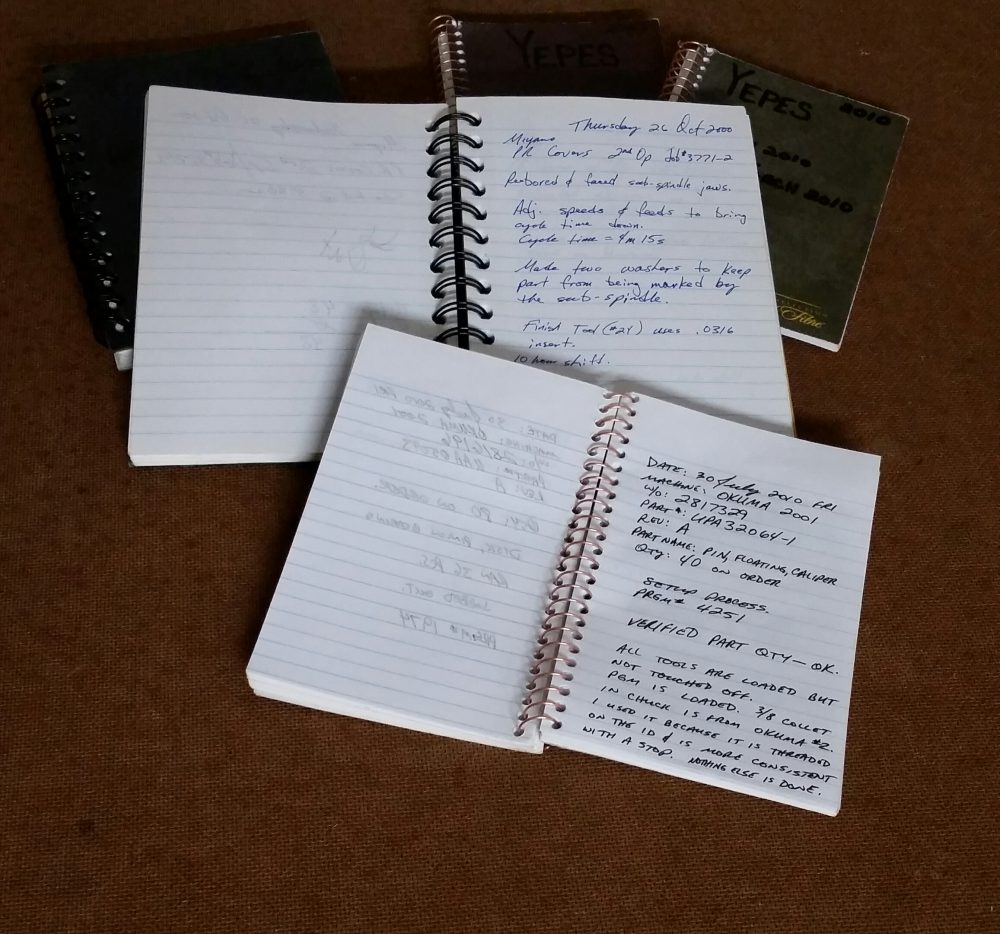

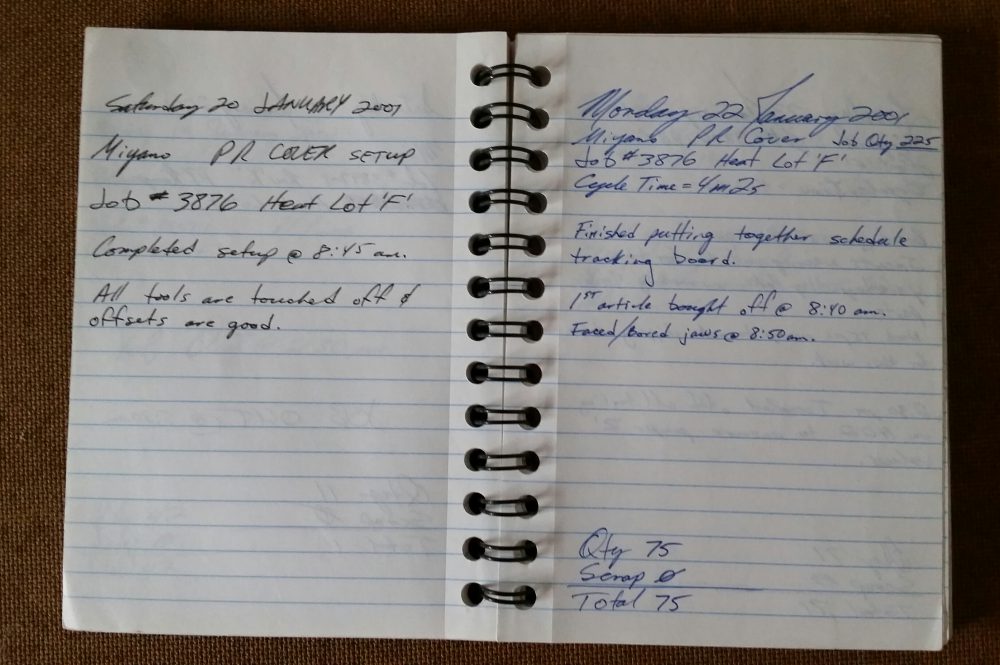

Question: What is a machining journal?

Answer: A machining journal is a daily log that records the many aspects of your workday in detail.

I’ve used machining journals since the beginning of my career as a machinist. I cannot tell you how many times those journals have come in handy. Sometimes you’re asked, ‘What did you work on three weeks ago on a Tuesday?’ Hell, sometimes I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning… and you’re asking me about three weeks ago? Out comes my journal. I can flip back to the day in question and accurately answer the question.

I’ve had bosses that approach me directly and ask about the material heat lot code on a specific material I machined sometime in the past. If they can give me a job number, I can give them the information they’ve requested. That’s important because, without the heat lot code, a job would have to be scrapped out. *Heat lot codes (traceability explanation below) are directly tied to certification codes. They are the way we establish traceability of a part from the original material supplier of the material, through the manufacturing process, and on to the customer. The jobs could be inexpensive or high dollar value. Once I relay the material certification number to my boss, he can then request hard copy ‘certs’ from the vendor of the material… saving the job from being scrapped.

Keeping a machining journal is helpful in other ways as well. I’ve had instances when a supervisor would tell me to proceed with a job that I don’t feel comfortable with running. It could be a tolerance not being called out on a print or maybe there’s a question about the finish. In either case, writing an entry into your journal and requesting that the supervisor sign off on the entry, puts the supervisor in the position to defend his decision on proceeding with the job, should it become an issue at some later point in time.

Times have changed a bit since I began my machinist career. I no longer keep a journal but will document concerns, etc. with emails. Even verbal conversations that center around a decision by a supervisor, an engineer, or programmer, are put into an email format and sent to all parties concerned. That way, should a decision later become a point of contention, the email chain can be then be resurrected to determine who said what.

*Traceability, through the use of heat/certification codes, are a requirement of nearly all high value parts supplied to the government, the aerospace industry, or other critical end customers. The reason for this requirement is that when a high value item fails, i.e. plane crash, etc. occurs, and the failure is traced back to a certain part… those high value items can then be pulled out of service to be inspected by investigators for flaws.